Blogs

July 04, 2020

Navigating The Choices…

Apps for cyclists

Want to map your trike ride or track your progress? Read on!There are a wide variety of smartphone apps available for today’s cyclists, and it can be challenging to choose the right one. Here is an overview of some of them, de- fined by categories, and a brief description of each. Some of the apps are free and some have a purchase or subscription fee. Use the link at the bottom of the article to get more details about these apps.

Navigation Only:

MAPS.ME – Features very detailed offline maps. Free.

Google Maps – The quality of routes is great for this very popular app. Free.

Tracking & Navigation:

Strava – #1 workout tracker for any kind of workout. Strava has a huge community of engaged and contributing members. Free and premium versions.

Map My Ride – A great application for cyclists, with similiar functions as Strava. Free and premium versions.

Bike Citizens – Local city guides (450 cities worldwide) with tracking and navigation. First region is free, extras are paid.

Outdoors:

ViewRanger – For outdoor cyclists who want excellent detailed maps.Topo maps available for Canada. Free. Detailed maps have fees.

Komoot – Helps you plan outdoor adventures. Offline maps plus turn-by-turn navigaiton. Integrates with other tracking apps. First region is free, more regions can be purchased in-app.

Computer Apps:

Bike Computer – Provides real-time data about your ride. Free & premium versions.

Cyclemeter – Provides very detailed data (graphs and maps) about your ride. Free plus in-app option to upgrade to Elite version.

Miscellaneous:

First Aid by British Red Cross – Complete instructions to perform first aid. Free. • Bike Doctor – Bike maintenance and repairs app. Detailed videos. $4.99

Relive – Create a great looking video of your ride by uploading data from track- ing devices and apps. Free.

This article was exerpted from a 2018 RidetheCity.com blog post. RidetheCity.com is a web resource that aims to be ‘your go-to guide for everything cycling related’. Read the entire article: http://www.ridethecity.com/blog/best-cycling-apps

June 27, 2020

From Sea To Shining Sea…

Imagine triking across the USA on a bike path!

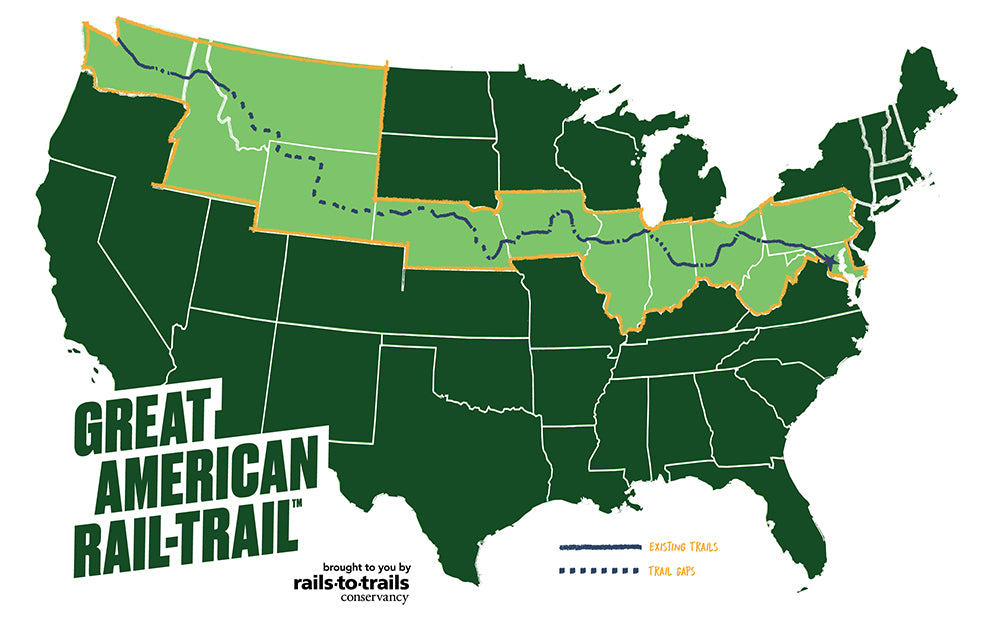

Add this one to your bucket list!The Great American Rail-Trail is an epic ongoing project to create an off road trail through scenic and historic routes across the entire USA! When completed, the trail will stretch from sea to shining sea – Seattle, Washington to Washington, D.C.

Announced in early 2019 by the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC), the Great American Rail-Trail will take an enormous amount of organizing and collaboration across federal, state and local municipalities. The masterplan for the trail is to utilize the extensive network of existing rail trails, as well as other multiuse trails. Over 50% of the route is already completed, thanks to decades of cycling advocacy work.

RTC’s late co-founder David Burwell is the visionary behind the Great American Rail-Trail. His dream was that one day cyclists could pedal “across this entire country… on flat, wide, off-road paths.” He wanted trail users to be able to trace American history along the country’s rail-trails, towpaths and greenways. Spanning 4,000 miles, the trail is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create an enduring gift for generations to come. This trail will truly become a ‘National Treasure.’

This article has been excerpted from the RailstoTrails.org website.www.greatamericanrailtrail.org

A Few Of The Connecting Trails Along The Way…

WASHINGTON D.C.

The Easternmost Endpoint For The Great American Rail-Trail Begins In Washington, D.C., At The Steps Of The U.S. Capitol. Heading West Through The National Mall, The Route Is Hosted By Trails Featuring Some Of America’s Most Renowned Landmarks And A Portion Of Rock Creek Park, The Oldest Urban Park In The National Park Service. After Traveling Through Historic Georgetown, The Route In D.C. Ends Near Fletcher’s Cove, A Well-Known Fishing And Outdoor Recreation Area Of The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park.

Read More

IOWA

The First State In The Nation To Put The Railbanking Act Of 1983 To Use, Iowa Has A Long History Of Leadership In Trail Development. Its Rich Network Of Trails Includes Well-Established Pathways Such As The Picturesque Cedar Valley Nature Trail—One Of The State’s First Rail-Trail Conversions And The State’s Great American Gateway Trail—And The Nationally Renowned High Trestle Trail With Its Famous Mine-Shaft-Themed Art Installation. These Trails Will Join With Dozens Of Other Trails To Create A 465-Miles-Plus Route From Davenport To Council Bluffs.

Read More

MONTANA

The Preferred Route Of The Great American Rail-Trail Through Montana Will Connect Communities Already Well-Known For Their Outdoor Recreation Assets—Including Livingston, Bozeman, Three Forks, Butte And Missoula. History Abounds Along The Route As Well: The Area Around The State’s Great American Gateway Trail—The Developing Headwaters Trails System In Three Forks—Has A History Stretching To Sacajawea And The 1804–1806 Lewis And Clark Corps Of Discovery Expedition; And In Livingston, The Highway 89 South Pedestrian Trail Travels Through The Original Gateway Town For The Country’s First National Park: Yellowstone.

Read More

June 07, 2020

Triking National Parks

Top Five Success For Cycling In National Parks

Reprinted from AdventureCycling.org

As we well know, there is no more authentic and exhilarating way to experience the grandeur and cultural significance of our national parks than by pedaling through them on a bicycle. So how did national parks work together with Adventure Cycling last year to improve biking? Check out our top five stories, and make sure to register a ride for the third annual Bike Your Park Day on September 29, 2018.

1. Shenandoah hosts its first car-free day with Ride the Drive.

The idea started with Crater Lake’s car-free day called Ride the Rim, when Adventure Cycling set up a conference call with the superintendents from Crater Lake, Shenandoah, and Glacier National Parks to talk about how the event came together. Two years later, within the first few hours of opening registration for Shenandoah’s Ride The Drive, it had filled with 4,000 eager participants. The event on April 23, 2017 opened up the northern part of Skyline Drive to biking and walking (and roller skating!), free of motorized traffic and its noise, fumes, and stress. About 1,000 participants showed up despite a bad weather forecast, but the rain held off and cyclists enjoyed their exclusive access to Skyline Drive’s spring splendor. The park is interested in hosting a second Ride the Drive, but determined that it needs outside funding and support to make it feasible.

2. Natchez Trace Parkway works to make cyclists safer with Share the Parkway campaign.

The Natchez Trace Parkway, the Natchez Trace Parkway Association (NTPA), and Adventure Cycling have partnered since 2013 on a Share the Parkway campaign to improve cyclists’ safety on the Parkway, in response to the death of local cyclist Gary Holdiness. Adventure Cyclist magazine published an article about this tragedy and how it sparked the campaign. We’ve worked for safety from many angles, including:

Visibility and enforcement. Thanks to funding from the NTPA, rangers are now giving away complimentary bike lights and high visibility vests to cyclists. Over 200 lights have been given away to help keep cyclists visible in the park’s frequent sun and shade transitions.

Signs. The USDOT Volpe Center published a study that provided recommendations for adding bike safety signs. In March 2017, the Parkway installed 53 “Cyclists May Use Full Lane” signs along the Parkway’s 444 miles.

Education and outreach. Brochures, website information, and radio and TV ads educate motorists and cyclists on how to safely share the road.

Data collection. Temporary bike counters were installed to gather data about bicycling visitation on the Parkway, and the parkway will be upgrading to permanent counters.

3. Glacier Park’s bike shuttle carries 1,500 bikes in its second spring biking season.

Adventure Cycling’s partnership with Glacier National Park has led to a number of improvements for biking in the Park, thanks in part to a $30,000 grant from the Glacier Conservancy. The park has increased its bike parking, now provides better online information about biking opportunities, and just completed its second successful spring biking season with the addition of a bike shuttle service to reduce parking congestion. The shuttle carried three times more riders (4,413) and bikes (1,470) in its second season than in 2016 when it was launched. It now also carries tandems and recumbent bicycles.

4. Shenandoah installs bike repair stands along Skyline Drive.

Shenandoah has been on a roll this year – in addition to Ride the Drive, the park installed three bike repair stands with bike pumps in key locations along Skyline Drive. The bike repair stations were funded by the Shenandoah Trust, which used a crowdfunding campaign to fundraise for the project. Given that it’s a trek to the nearest bike shop from the park, these tools will be helpful in a pinch.

5. The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Towpath receives $1 million for surface improvements.

If you’ve ridden the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Towpath, you might have noticed that sections of it are looking pretty rough. Adventure Cyclist featured an article about the Towpath and its funding and maintenance issues in 2015, and we’ve provided support for the park’s efforts to solve these issues. The park learned in December 2017 that it was receiving $1 million of Transportation Alternatives Program grants (a federal funding source) for surface improvements to 12 miles of the Towpath from Shepherdstown to Harpers Ferry. The National Park Service will match the TAP funds with $472,000. This is the first phase of five improvements, and while funding for the next four phases isn’t guaranteed, it’s a good sign.

A Repair Stand And Bike Pump Provide Emergency Bike Maintenance Along Skyline Drive.

Skyline Drive Is Quieter Than Usual For Ride The Drive, Shenandoah’s First Car-Free Day.

A Car-Free Going-To-The-Sun Road Is The Ride Of A Lifetime During Glacier Park’s Spring Plowing.

The 184-Mile C&O Canal Towpath Is A Popular Trail For Bike Touring.

A Bike Light And High Visibility Vest Giveaway Makes Cyclists More Visible On The Natchez Trace.

May 29, 2020

Mini Road Test: Greenspeed GT20

By Alex Strickland – AdventureCycling.org

“How fast can I take a turn?”

Embarrassingly, this was my first thought after plopping down in the seat of Greenspeed’s new folding GT20 recumbent tadpole trike. It was the first time I’d ever settled into such a machine, and its low-slung position and airplane-like hand controls had my mind racing to, well, racing. Which is exactly what I did — until I very nearly capsized in a too-zealous turn and decided that crashing Greenspeed’s prototype would be frowned upon by the friendly Australian recumbent makers.

I’ve been riding bikes with some level of sincerity for almost 20 years, but until this summer I had never piloted a recumbent of any type. In fact, until joining Adventure Cyclist a few years ago, I’m not sure I’d ever even seen more than a handful of recumbents. But the laid-back lobby isn’t always so, and on more than one occasion I’ve received an earful from a recumbent rider concerned that we weren’t giving the ‘bent its due.

So after Greenspeed exhibited at Adventure Cycling Association’s Montana Bicycle Celebration this summer and offered to leave a prototype model with me for a few weeks, I couldn’t say no. The GT20, a folding, 20-inch–wheel trike modeled after their popular Magnum series, sports a square-tubed mast to resist twisting, a 3×8 drivetrain, drum brakes, Greenspeed’s lauded seat, and enough quick releases to make my head spin.

Fast forward for a moment to prepping the GT20 for its next destination — I recovered the shipping box Greenspeed had left, set it next to the bike, and uttered a long tirade. How, I profanely wondered, was this medium-sized bike going to fit into this decidedly small-sized box? Those quick releases were the answer, and after a bit of figuring (and the removal of both front wheels), the trike was packed up and ready for shipping. It was perhaps the most impressive full-size folding mechanism I’ve seen.

But those quick releases come at a cost, and that’s rigidity. The sextet of quick releases used to adjust the cockpit controls (two for the seat angle, two for the mast, and one on each side for the steering arms) were prone to slippage if I got overzealous at the controls or on the power. Some of this was certainly user error, and as I settled into riding the GT20 over the first week, the slip frequency dropped sharply as I began to use more subtle inputs and resisted some knee-jerk movements that had caused issues early on.

In fact, subtle inputs proved to be the key to getting the most from the Greenspeed. A light touch on the steering arms, a gentle feather of the inside turning wheel’s brake (the right and left brakes are operated independently), and a downshift-and-spin cadence instead of trying to mash big gears combined to make the experience downright dignified. It was a big upgrade from my first few days on the trike, where I no doubt looked like a lunatic as I wiggled my way down the road, locked up the brakes, and was forced to stop and re-adjust after pushing too hard against some part of the trike and causing a bar to slip.

If I sound generally underwhelmed, that’s not quite right. Somehow the sum of these rather unusual (to me) parts added up to something that was undeniably fun. And it wasn’t just me. I’d estimate that half of Adventure Cycling staff took the Greenspeed for a spin on the surface streets around our offices, and they all seemed to return a bit bewildered but grinning. The little trike is infectious, and for those of us used to sitting atop a diamond frame, there’s a certain something about the low-slung position and different steering inputs that’s instantly a blast.

As for the nuts and bolts of the thing, the highlight of the component spec was the Shimano Ultegra bar-end shifters, which managed the 8-speed Alivio rear derailer and Microshift triple front with the perfect action and feel you’d expect from Ultegra-level components. In fact, I’d say shifting the front derailer on the Greenspeed — on full display right in front of you while riding — was perhaps the best front shifting experience I’ve ever had. Left and right Sturmy Archer drum brakes were fine, though I still think I’d prefer mid-level mechanical discs for better modulation. Of course that would have an effect on how the front wheels popped off and stowed, so the drums make sense on this particular model. Greenspeed’s own 20 x 1.5in. slicks were fine rubber for tarmac, but a few short excursions onto gravel quickly set the tires into “drift mode.” Fun, yes, but probably a bit outside the performance envelope the company’s engineers recommend.

It wasn’t so much the tires themselves but the diameter of the wheels they wrapped that I found was perhaps the most singular feature of the so-named GT20. Twenty inches proved very susceptible to the expansion gaps, potholes, and pock-marked cobbles that characterize my favorite Missoula test loop, delivering a jolt when the small hoops were sucked into various obstacles. Some of this was rider error, to be sure, as I found I had a penchant for splitting potholes right between the front wheels and getting shocked out of my self-congratulatory smugness by the rear wheel catching the impediment with perfect accuracy.

This mini road test feels all over the place, which closely mirrors my thoughts on the little Australian trike. Riding the GT20 in town behind angle-parked cars and up to intersections with poor sightlines was among the most vulnerable I’ve ever felt on two (or three) wheels. But spinning along a bike path or an open road was a blast, and a comfortable one at that. I ride a lot of eye-catching bikes, but none has ever received more comments than the Greenspeed, which, depending on your point of view, could be a pro or a con. The GT20 packs small, delivers some grins and some small frustrations, and if you’re feeling frisky is more than happy to go through a corner in a manner that’s reminiscent of a kid putting a go-kart through its paces. In short, I came to feel the way about the Greenspeed that I feel about the eBikes I’ve ridden over the years: not for everyone, but surprisingly fun and a great fit for the right rider.

May 10, 2020

Hot Wheels: Today’s Adult Tricycles Are Low, Sleek, Speedy, And Finding A Larger Fan Base

By Stephanie Kanowitz And Originally Posted On The Washington Post On Oct. 9, 2018

With sweat beading on a hot August morning, Howard Quinn of Catonsville paced the pavement at Mt. Airy Bicycles in Carroll County, Md., studying recumbent tricycles that he and his grandson, Freddy, could share. After neck surgery, Quinn tires quickly on a bike, and the boy has trouble balancing on a two-wheeler.

“It’s in first gear,” Tom Hill told Freddy, situating him on a seven-gear Delta model priced at $1,399. “Here’s your hand brake.” He sounded like a salesman, but Hill, 61, of Damascus in Montgomery County, doesn’t work at the shop. He’s a customer — a frequent customer, having bought three trikes in nine years after undergoing back surgery.

“I like this better. My back doesn’t hurt; my upper body isn’t tired from having to control the bike,” Hill said.

Customer Lynn Carr, 70, a former bike rider and runner, is less enthusiastic. “You really can’t get the same level of aggressive riding as you can on a two-wheeler, just simply because on a two-wheeler you can stand up on the pedals and really get after it,” he said. “Here, you’re sitting.” But riding a trike enables the Mount Airy resident to stay active after two hip replacements and three back surgeries. Carr rides more than 100 miles a week.

Trikes for adults aren’t new, but they’re finding a larger fan base among recreational and more serious cyclists. Sleeker, more aerodynamic, lower-to-the-ground designs are a far cry from the traditional “granny trikes,” with three 26-inch wheels, high seats and large baskets in the back, though those are still around.

“As an overall category, trikes are growing,” said bike expert Jay Townley, futurist at the Human Powered Solutions Group, a consultancy of bike industry veterans that formed in June. “But the big growth is not in the old, traditional upright trike,” he added. “The growth is in what is referred to as a recumbent trike, or tri.”

No group seems to keep statistics on the niche market that is adult tricycles. But shop owners and manufacturers say they are seeing an increase in sales. For example, TerraTrike, which has been making adult trikes since 1996, has seen at least 10 percent growth — and as much as 40 percent — each year. And three trike brands — Catrike, Sun Bicycles and TerraTrike — were represented last year on the National Bicycle Dealers Association’s list of the top 40 bike brands that specialty bike shops sell.

Trikes for adults come in a variety of models and styles. Some are made for speed, some have more upright seats for riders who don’t want to lean back, and some aren’t quite so low to the ground, to make it easier to get on and off. They range widely in price, including one-speed classic uprights with a basket for about $400, and 30-speed recumbents with aluminum frames for around $4,000.

The main market driver is an aging, health-focused population, but also, recumbent “trikes are cool,” said Larry Black, owner of Mt. Airy Bicycles, who has been in the business for 39 years. “It’s like a go-kart or a roller coaster,” he said. “You’re low to the ground.”

Recumbent cycles have a lower center of gravity than upright ones, which makes them more stable and comfortable, said Jeff Yonker, marketing director at Michigan-based TerraTrike.

“It’s like sitting in a beach chair,” Yonker said. “We find that people will actually do as much or more exercise riding as [they would on] an upright bike because they don’t have the pain involved, and so they tend to ride longer and farther.”

The ergonomics of recumbent bicycles and tricycles are the same, but trikes are easier to balance and don’t tip when you stop, said Wayne Sosin, president of Worksman Cycles, based in Queens. Unless, that is, you’re not watching your pace. Whether two- or three-wheeled, recumbent cycles can be surprisingly speedy because of their low profile. “We’ve seen a lot of people crash them by going too fast,” Black said. “The stability is very limited on a trike at high speeds.”

At Black’s two stores, recumbent trikes are outselling recumbent two-wheelers about 10 to 1, and they’re outselling upright trikes at about the same rate. Upright trikes aren’t extinct, however, and offer great utility in some settings.

Sosin, of Worksman Cycles, which has been making adult trikes since its founding in 1898, said one of its main markets for heavy-duty uprights is industrial facilities. “If you walk into a Ford Motor Co. — or the Pentagon, for that matter — you’ll see workers riding around on real heavy-duty tricycles — not really consumer-appropriate, but more for rugged commercial use,” Sosin said.

The company’s upright models for recreation are also in high demand. “Recumbents are far more expensive and far more specialized and far more performance-oriented, but the traditional adult tricycles dominate the demand by consumers,” Sosin said. “Baby boomers, active seniors are probably buying traditional adult tricycles 100 to 1 over recumbents.”

On roads, tricyclists, like bicyclists, must follow traffic laws. They also must follow local bike regulations on helmet and light or reflector use. Trikes also can share bike lanes.

But Black warns against riding recumbent trikes alongside cars. “It’s dangerous because your head is below the average car fender — that’s now an SUV, pickup or minivan — and you can’t see,” he said. “You could put flags and lights on the trike, but it’s your ability to see that’s compromised.”

When Quinn returned from his test ride in Mount Airy, he was beaming. “This is fantastic. This is something that we could both do,” he said, thinking of his grandson. A few weeks later, he returned to the shop and bought a recumbent trike.

May 03, 2020

Recumbent Versus Standard Bikes

By Siegfried Mortkowitz And Originally Posted On We Love Cycling October 17, 2019

The idea of cycling while lying down was born not long after bicycles became popular in the late 19th century, for the simple reason that anything worth doing should be done as comfortably as possible – and pedalling while lying on your back would theoretically make it easier on the rider over long distances. After all, it’s like pedalling in bed.

Recumbent bikes are faster because the recumbent position creates less vertical surface for air to push against and is therefore far more aerodynamic. © mastersky / DPphoto / Profimedia

The first recumbent bike was the Fautenil Vélociped, made in France in 1893, but it and subsequent models did not stir much public interest. It wasn’t until the 1930s that recumbent bicycles drew significant attention, primarily because the French bicycle maker Charles Mochet, who manufactured several customizable models of recumbent bikes, hired professional cyclists who used his bikes to win important races, both on the road and on the track.

Mochet’s Vélo-Velocar broke several records, including fastest bicycle, fastest average speed and a number of long-distance records. However, the cyclist governing body at the time, Union Cycliste Internationale, made it illegal to use recumbent bikes in events where standard bicycles were used, which almost totally destroyed the popularity of recumbent bikes for decades.

Recumbent bicycles became popular again in the 1970s with the establishment of several sporting events that popularized this form of cycling. In 1979, the first mass-produced modern recumbent bicycle was put on sale, the Avatar 2000. This model and several of its competitors broke several records during the next 10 years, increasing the popularity of recumbent bikes around the world. In the 1980s, the first electric models were introduced, and early in this century international organizations began to admit that recumbent bicycles easily outperform upright bicycles over long distances.

© Oleksandr Rupeta / Zuma Press / Profimedia

However, it’s still fairly unusual to see someone cycle past you while lying on his or her back. And, if you’re like me, you wonder why people do it. Is it just because it’s easier or does riding a recumbent bike provide benefits the standard upright bike does not?

Apparently, it does. The most obvious advantage is in case of accidents. Because you are riding closer to the ground than on a standard bike, your fall will be less painful and, barring a really bad collision, the impacts will be to the lower body rather than the head. Also, because the centre of gravity is lower than on an upright bike, braking distances on a recumbent are shorter and without the risk of rear-wheel lift.

The recumbent bicycle is also much easier on the rider’s back and neck. In addition, on some recumbents the rider’s legs are at nearly the same height as the heart, which improves circulation and increases endurance and power output over long distances. Breathing on a recumbent is easier too because the rider is not bent over, as he is on a standard bike.

Riding in a recumbent position also puts far less stress on the bones, tendons, joints and ligaments because the rider’s weight is spread over a larger area (though it does put more stress on the core muscles and the hamstrings). Also, some studies have indicated that riding an upright bicycle may be a cause of male impotence because of the pressure placed on the perineal nerve by the saddle. Recumbent seats don’t have this issue.

© Martin Remmers / AFP / Profimedia

And, finally, recumbent bikes are faster because the recumbent position creates less vertical surface for air to push against and is therefore far more aerodynamic. You don’t have to lean over the handlebars or wear specially designed helmets to cut air resistance.

But the recumbent also has a few disadvantages compared to the standard bike, the most important being visibility: it’s harder for the recumbent rider to see the traffic and the view can more easily be obscured by fences or parked cars. In addition, it’s harder for the recumbent rider to look back.

Conversely, because the recumbent rider is not upright, she is harder to see by oncoming or turning vehicles – though some riders say that being on the same level as drivers and seeing eye-to-eye with them is an advantage. To deal with this issue, many recumbent cyclists simply add colourful pennants or reflective material to their bikes to make themselves more visible.

April 25, 2020

National Study Reveals U.S. Cycling Behaviors During Coronavirus Pandemic

From TrekBikes.com

Data indicates Americans are turning to cycling for mental and physical health as well as an alternate means of essential transportation during COVID-19

As many Americans across the country are facing extended social distancing orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers are turning to cycling as an alternate means of essential transportation, for mental and physical health, and to keep the kids busy.

Today, Trek released new results from a nationally representative survey of over 1,000 American adults 18-years-old and over, conducted in partnership with research firm Engine Insights. The study explores how cycling behaviors and attitudes are shifting amidst the Coronavirus pandemic, with results revealing that bike riding is perceived as a “safer” activity and mode of transportation compared to public transit, and more people are biking than before.

Of Americans who own a bike, 21% of them have been riding more since the COVID-19 pandemic. This can be traced back to a need for less public and crowded forms of transportation, a need for exercise, or just a plain old desire to have a bit of fun while adhering to social distancing in an otherwise stressful time. Study findings also reveal that cycling’s popularity is likely to prevail, with half of Americans (50%) planning to ride their bike more after the COVID-19 pandemic is over.

“Our country is facing an unprecedented health crisis that has impacted all aspects of society and culture, and how we move. At Trek, we’re curious to pull back the curtain to see how Americans are adapting to the new normal and if their attitudes and behaviors around cycling have shifted given that people are under more stress than ever before, feeling cooped up and seeking alternate modes of essential transportation that’s in line with social distancing,” said John Burke, President of Trek Bicycle.

“Exercise is key to not only physical health, but mental health as well, and it was encouraging to see that nearly one-third of Americans are turning to bike riding to destress and help cope with the current environment. We want to continue supporting people in both urban and rural areas, and in between, with viable transportation options and a hobby that keeps them, and their kids occupied, healthy and happy during these difficult times.”

Among key findings the study revealed that:

Amidst COVID-19, people would prefer to travel by bike

85% of Americans perceive cycling as a safer mode of transportation compared to public transportation while social distancing

If Americans must travel within 5 miles during COVID-19, 90% included biking in their top 3 primary modes of transportation

14% of Americans bike ride to replace public transportation

Cycling supports mental health during the current environment

Nearly 2/3 of Americans (63%) feel bike riding helps to relieve stress/anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nearly 1/3 (27%) of Americans who own a bike turn to bike riding for mental health and/or to destress

More Americans are turning to cycling for physical exercise

41% of Americans feel exercise and fitness are the most important motivation to ride their bike during the COVID-19 pandemic

Over 1/3 (38%) of Americans who own a bike use cycling as their source of exercise

Read the entire article here.

April 19, 2020

When A Recumbent Trike Levels The Playing Field

By Kyle Bryant And Originally Posted On The Huffington Post December 6, 2017

<img "="" src="https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0557/1405/4276/files/2015-12-18-1450410298-8099881-KyleBryantCatrikeBW-thumb.jpg?v=1646881152">The first few pedal strokes feel refreshing as my heart rate picks up and blood circulates through my legs.

It had been months since I got on my Catrike with any consistency, and I was out of shape.

In July I rode up the highest paved road in North America – a ride that I had been anticipating for a few years.

I rode about 1,200 miles this year to prepare for Mt Evans but since the summit I have logged no more than 200.

Now about 5 miles into my Thanksgiving ride with my Dad, I am starting to feel the effects of inactivity. As we begin to climb the first sustained hill on our 17-mile ride our speed drops significantly, my cadence slows, and my legs feel like jello.

My Dad, who rides an upright bike, passes me and says: “You’re a little sluggish today.”

“See you on the downhill,” I reply.

Don’t Blame it on the Recumbent

At times like this it’s easy to blame the lack of uphill speed on the fact that I ride a recumbent trike.

But this belief feeds into the mental divide in cycling circles—a belief that says recumbents are “second-class” bikes.

Most people have the impression that recumbent riders are out-of-shape old men. The cycling community even has a name for these riders: FOG (Fat Old Guy). But I’m not old… or fat. I’m a 34-year-old disabled athlete, who’s biked across the United States, both competitively and in the spirit of adventure.

Whether you are a FOG, a Category 1 racer, or a disabled athlete, we all have challenges.

Challenges unite every rider.

Lack of Leverage and Resistance Impact a Recumbent Rider

On a recumbent, you’re unable to stand up over your pedals to shift your weight (like an upright) and use gravity to your advantage. Instead, all your power depends upon the strength of your legs.

Also, the greatest source of resistance on any bike is in the wheels. With three wheels, I have 1.5 times the resistance.

So, as I’m crawling up the hill with my dad, the effort requires me to overcome both of these obstacles.

When we reach the top of the hill, each pedal stroke creates some speed, and I start to make some ground. When we start down the descent, my aerodynamic advantage takes over and I speed past Dad.

“Catch me if you can,” I shout.

He does… at the next uphill.

Sometimes I wish I could ride an upright bike and keep more consistent pace with my Dad, Brother, Uncle Steve, and so many cycling friends that I have made over the past 10 years.

Down the next hill I stop pedaling as I coast at 25 mph with the chilly wind in my face and the warm sun on my cheeks.

Train for the Advantages… and the Disadvantages

My trike is a tool that helps me even the playing field, sometimes, even shift the momentum in my favor, depending on my effort and preparation.

We each have our own unique set of challenges. Each person struggles to keep moving forward, whether that means getting a few more mph out of your legs or just getting out of bed.

I have come to love cycling because I am constantly in competition with myself, trying to get better all the time. If I have a poor performance by the standards I mentally set for myself, there is nobody to blame but me. I can usually trace it back to my diet, or sleep, or inactivity.

When we get back to the house, I pull into the driveway slightly in front of my Dad, and we are both exhausted and satisfied. We both pushed ourselves and kept moving for 17 miles.

Whether we are on two wheels or three, we all struggle to keep moving.

The reward lives in the effort.

(Photos by Blake Andrews, SLOtography.com)

Kyle Bryant’s book titled Shifting Into High Gear can be found wherever books are sold including Amazon.com

April 07, 2020

Journey Of A Lifetime… Second Time Around

Our first ride across Canada…

In 1999, my wife Laurel McLaughlin fulfilled a childhood dream and crossed an item off of our shared bucket list. We pedaled our mountain bikes 8,045 kms across Canada, from Vancouver, British Columbia to St. John’s, Newfoundland. We loved the adventure, and the slow pace was the perfect way to take in the Canadian landscape. It was also the perfect way to experience kindness and generosity on a near daily basis. In Saskatchewan, a pleasant woman offered her home for us to spend the night. In New Brunswick, an elderly gentleman insisted on giving us $20 to buy lunch, and while gravel pit camping in rural Newfoundland and Labrador, a couple who were, “on the brown envelope,” welcomed us into their cramped but cozy trailer to share homemade bread and strawberry jam.

The ride had its share of struggles and anxious moments. It seemed to take a lifetime to climb the mountain passes in British Columbia, and in Ontario it was often a balancing act while trying to ride a thin strip of shoulder alongside the constant flow of traffic. Laurel came within an inch of colliding with a black bear when careening down a steep mountain slope in British Columbia. The bear, luckily, was more startled than Laurel, and made a quick about face back into the bush. In another instance, we waited anxiously before a nearby cougar decided that we were no longer worth its steely-eyed attention.

‘Turtles of the Road’ and a new plan ahead

Laurel and I have always characterized ourselves as the turtles of the road. We ride slowly, but with determination — we enjoy smelling the roses along the way. Eventually, though, after two and a half months, we completed what had been meant to be our “journey of a lifetime.” St. John’s Harbor and the Atlantic Ocean were beautiful sights to behold, but we hadn’t arrived without some sadness that our journey had ended.

Since that time, Laurel and I have ridden our bikes together to San Francisco, Chicago, throughout Manitoba, Saskatchewan and North Dakota, in western Ireland and along the North Sea in England. About three years ago we decided that it would be fun to repeat our original cross-country ride. Already nicely into our sixties, it would be, in all likelihood, even more challenging than the first time. We weren’t really sure if we were up to the task, but we were both game to try. Two years seemed like adequate prep time at that point. We would fly to Vancouver with our bikes and trailer disassembled and in boxes in the late spring of 2017. As before, we would reassemble the bikes and trailer at the airport and begin pedaling east. That was the plan.

From headaches to stroke…

In early August, 2016, the plan changed. Laurel had always had occasional, severe headaches, but this one was different, even more severe, and more persistent. Neurologists call it a “thunderclap headache.” After days of “feeling off,” a visit to the doctor and a subsequent, urgent referral to the emergency department of the Brandon Regional Health Centre, confirmed that Laurel had experienced a hemorrhagic stroke — a brain bleed. From there, she was quickly transported by ambulance to the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre for further testing.

Over the course of the weekend, the MRI and CT scan came up empty: there was no visible evidence of an anomaly, apart from the bleed itself. Medical opinion suggested that Laurel’s hemorrhage may have been a “one off” and that she might never experience another episode. Laurel was also improving on a daily basis. Her headache had disappeared and her slightly hesitant speech pattern was diminishing, as was her trace of disequilibrium. She was almost back to her old self. A bit embarrassed, she joked that she felt like a fraud for taking up a bed. With one final test, a cerebral angiogram to confirm the presence or absence of a malformation or aneurysm scheduled for Monday, we expected to be back home in Brandon later that afternoon.

Living day by day

No one thinks that they’ll be that one-in-one-hundred person. Laurel, unfortunately, drew the short straw. The catheter used for the cerebral angiogram caused what was described by neurologists as a “shower of emboli,” producing multiple, additional strokes. Laurel was left paralyzed and unable to effectively swallow. Her hearing, vision and speech were impaired, and she had difficulty staying awake. My sister-in-law, a pediatric intensive care nurse from Ottawa, was alarmed enough by Laurel’s depleted oxygen levels that she advised me to “prepare” our three adult children. It was only sometime later that I was able to process what she had actually meant. I wasn’t prepared myself. Laurel had always been the strong and fiercely independent one, and the possibility of her death had never crossed my mind. In fact, a few years before, I had taken great pains to provide her with pension details, passwords, and photographs and songs that I wanted shown and played at my funeral. I was confident that she would outlive me. No, I wasn’t ready for Laurel to die.

More important, Laurel wasn’t ready. After ten days in intensive care, Laurel was transferred to the stroke recovery unit at Brandon’s Assiniboine Centre. We knew that the most dramatic improvements, if they were to occur, would likely take place within the first three months following the strokes. On cue, and with the guidance of the fine rehabilitative team at the Assiniboine Centre, Laurel began to improve. We celebrated the first time that Laurel was able to move her paralyzed right hand, and when she had her feeding tube removed and replaced with a carefully monitored pureed diet. And, we were ecstatic when Laurel was able to move her right leg, and with the help of three physical therapy team members, was able to walk a path between two parallel bars.

Determination and the road to recovery

By the time of her discharge in late October, Laurel was able to travel short distances with a walker. With care, she could slowly consume solid food. Her strength had measurably improved. Laurel remained paralyzed on the left side of her face, so that her speech and vision, though improved, continued to be affected. Over the next year and a half, the Brandon Shoppers’ Mall became Laurel’s therapy centre. We walked the mall on a daily basis, increasing distances over time. Laurel also incrementally increased her level of independence, moving from total reliance on her walker to part time reliance — she would use the walker for three “laps” and hold on to my hand over an additional three laps.

Laurel’s recovery was aided by the community of friends that we developed while walking regularly at the mall. They consisted of other walkers, mall employees and folks who would frequently meet to have coffee in the food court. They became Laurel’s informal support system. Whether with a smile and nod, a thumbs-up, or an encouraging comment, they cheered each sign of progress.

At some point during Laurel’s informal rehabilitative process, we decided to resume cycling. We knew that disability and inability are not the same things, and we figured that by adapting to meet Laurel’s current needs we could once again enjoy cycling together. Because of her poor balance and limited vision, Laurel could no longer independently ride a bicycle, so, after doing our online research, the adaptation that we came up with was a tandem recumbent trike. With the tandem’s independent pedaling system, we could ride together, but we could still pedal at our own, preferred rates (Laurel’s preferred pedaling rate has almost always been faster than mine).

Z6 USteady & rolling again on 3 wheels

While we continued to walk at the mall during the summer of 2017, now, we also cycled. Our 10-foot-long TerraTrike Tandem Pro caught the attention of many onlookers as we pedaled the streets of Brandon. Children were particularly unguarded in their enthusiasm. With the trike’s multiple flags to increase visibility, we felt a bit like the advanced guard for the Travelers’ Day Parade.

By summer’s end, Laurel’s endurance had increased to the point that we could count five return trips to Carberry and an overnighter to Virden, Manitoba as notable cycling achievements. We rekindled the idea of once again riding across Canada. Over time, however, we decided to modify the trip, and instead, pedal from Brandon to Halifax, N.S. So, on May 26, 2018, at ages sixty-eight and sixty-five, we hitched our trailer to the back end of the trike, and we began pedaling east down the TransCanada Highway. On July 30, after riding 4,600 kms. (2,850 miles) through five provinces and four states, and one day before the two-year anniversary of Laurel’s original stroke, we arrived in Halifax.

Sweltering heat had seemed to follow us from west to east, and at times the only shade to be found was in the shadows cast by telephone poles. Laurel’s determination, however, never wavered. It didn’t waver in the extreme heat or while getting soaked to the bone by occasional downpours. It didn’t waver when climbing New Brunswick’s edition of the Appalachian Mountain range, or any of the other steep slopes that we encountered. And, it didn’t waver when she was unceremoniously dumped from the trike on at least three occasions, including the time that we scrambled chaotically to escape a car that seemed intent on backing over us. There were no blue ribbons or trophies at the end of our journey, only the bumps and bruises that Laurel had sustained along the way, and the deep satisfaction that just shy of two years after Laurel’s original stroke we had completed our real journey of a lifetime.

Throughout our journey, we were often stopped by people interested in the fourteen-foot ‘train’ that we were pedaling, and in Laurel’s story of resilience. “You’ve got a lot of guts lady,” and “You’re an inspiration” were impressions that people often shared after meeting Laurel. Though she’s forever a humble and unassuming person, Laurel’s hope is that her story might also provide some measure of inspiration for others who have experienced a stroke and who are currently on their own journey of recovery.

Read the original article on the Brandon Sun.